Q: What is the story of “&” and why is it replacing “and”?

A: The “&” character, or ampersand, is seen a lot these days in texting, email, and online writing, but the use of a special character for “and” isn’t a new phenomenon. English writers have been doing this since Anglo-Saxon days, a usage borrowed from the ancient Romans.

In his book Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols & Other Typographical Marks (2013), Keith Houston writes that the Romans had two special characters for representing et, the Latin word for “and.” They used either ⁊, a symbol in a shorthand system known as notae Tironianae, or the ancestor of the ampersand, a symbol combining the e and t of et.

The Tironian system is said to have been developed by Tiro, a slave and secretary of the Roman statesman and scholar Cicero in the first century BC. After being freed, Tiro adopted Cicero’s praenomen and nomen, and called himself Marcus Tullius Tiro.

Houston says the earliest known recorded version of the ampersand was an et ligature, or compound character, scrawled on a wall in Pompeii by an unknown graffiti artist and preserved under volcanic ash from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

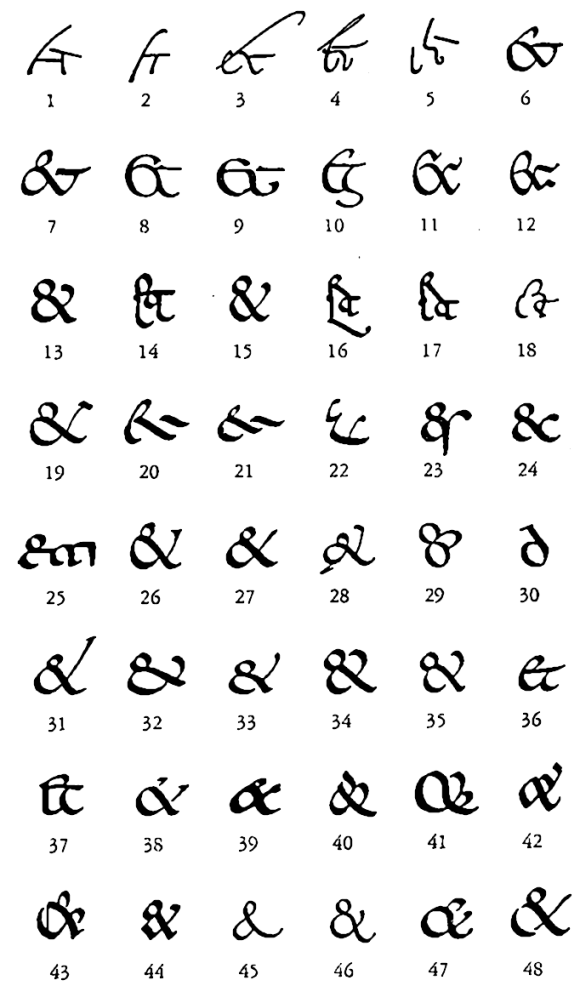

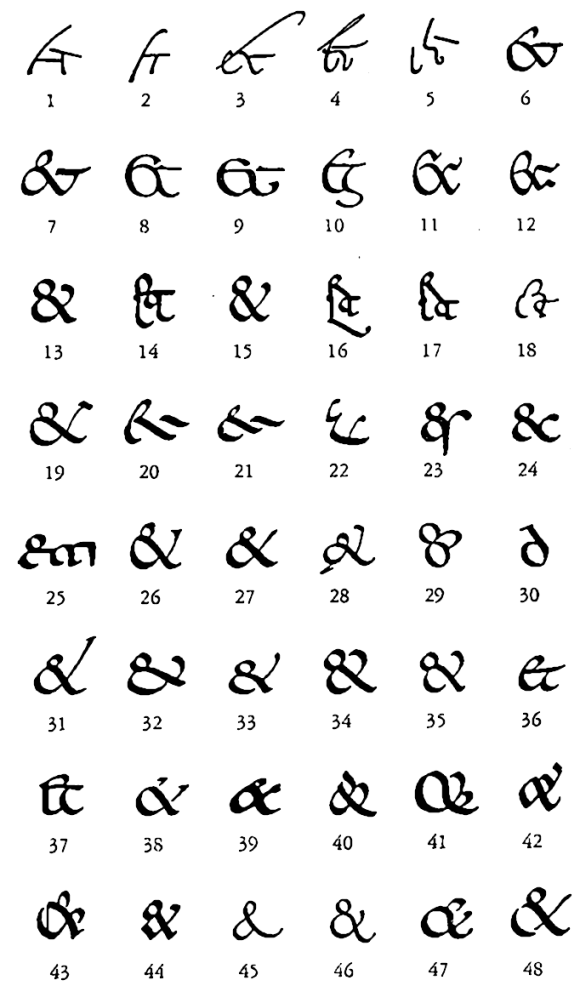

He cites the research of Jan Tschichold, author of Formenwandlungen der &-Zeichen (1953), which was translated from German to English in 1957 as The Ampersand: Its Origin and Development. An illustration that Houston based on Tschichold’s work shows the evolution of the ampersand over the years.

(Image #1 is from Pompeii, while the modern-looking #13 is from the Merovingian Latin of the eighth century.)

In Shady Characters, Houston describes how the ampersand competed with the Tironian ⁊ in the Middle Ages. “From its ignoble beginnings a century after Tiro’s scholarly et, the ampersand assumed its now-familiar shape with remarkable speed even as its rival remained immutable,” he writes.

“Whatever its origins, the scrappy ampersand would go on to usurp the Tironian et in a quite definitive manner,” he says, adding, “Tiro’s et showed the way but the ampersand was the real destination.”

Today, Houston writes, the Tironian character “survives in the wild only in Irish Gaelic, where it serves as an ‘and’ sign on old mailboxes and modern road signs,” while the ampersand “ultimately earned a permanent place in type cases and on keyboards.” (We added the links.)

Although the ampersand was common in medieval Latin manuscripts, including works written in Latin by Anglo-Saxon scholars, it took quite a while for the character to replace the Tironian et in English. In most of the Old English and Middle English manuscripts we’ve examined, the Tironian symbol is the usual short form for the various early versions of “and” (end, ond, ænd, ande, and so on).

A good example is the original manuscript of Beowulf, an epic poem that may have been written as early as 725. The anonymous author uses ond for “and” only a few times, but the Tironian symbol appears scores of times. However, modern transcriptions of the Old English in Beowulf often replace the “⁊” with ond or “&.” When the Tironian character does appear, it’s often written as the numeral “7.”

Here are the last few lines of the poem with the Tironian characters (or notes) intact: “cwædon þæt he wære wyruldcyning, / manna mildust ⁊ monðwærust / eodum liðost, ⁊ lofgeornost” (“Of all the world’s kings, they said, / he was the kindest and the gentlest of men, / the most gracious to his people and the most worthy of fame”).

Although you can find dozens of ampersands in transcriptions of Old English and Middle English manuscripts, an analysis of the original documents shows that most of the “&” characters were originally Tironian notes.

Dictionaries routinely transcribe the Tironian note as an ampersand in their citations from Old and Middle English. As the Oxford English Dictionary, the most influential and comprehensive etymological dictionary, says in an explanatory note, “In this dictionary the Old and Middle English Tironian note ⁊ is usually printed as &.”

However, the ampersand does show up at times in early English. For example, it’s included in an Anglo-Saxon alphabet dating from the late 10th or early 11th century. A scribe added the alphabet to an early 9th-century copy of a Latin letter by the scholar, cleric, and poet Alcuin of York (British Library, Harley 208, fol. 87v).

The alphabet is in the upper margin of the image. It includes the 23 letters of the classical Latin alphabet (with a backward “b”) followed by the ampersand, the Tironian et, and four Anglo-Saxon runes: the wynn (ᚹ), the thorn (þ), the aesc (ᚫ), and an odd-looking eth (ð) that resembles a “y.” At the end of the alphabet, the scribe added the first words of the Lord’s Prayer in Latin (pater noster). The British Library’s digital viewer lets readers examine the image in more detail.

At the end of Harley 208, which includes copies of 91 letters by Alcuin and one by Charlemagne, the scribe wrote a line in Old English, “hwæt ic eall feala ealde sæge (“Listen, for I have heard many old sagas”), which is reminiscent of line 869 in Beowulf: “eal fela eald gesegena” (“all the many old sagas”). Is the scribe suggesting that the letters are ancient tales?

A similar alphabet appears in Byrhtferð’s Enchiridion, or handbook (1011), a wide-ranging compilation of information on such subjects as astronomy, mathematics, logic, grammar, and rhetoric. However, the alphabet in the Enchiridion (Ashmole Ms. 328, Bodleian Library, Oxford), differs somewhat from the one above—the æsc rune is replaced by an ae ligature at the end.

We’ve seen several other Old English alphabets arranged in similar order. In most of them, an ampersand follows the letter “z.” Fred C. Robinson, a Yale philologist and Old English scholar, has said the “earliest of the abecedaria is probably” the one in Harley 208 (“Syntactical Glosses in Latin Manuscripts of Anglo-Saxon Provenance,” published in Speculum, A Journal of Medieval Studies, July 1973). An “abecedarium” (plural “abecedaria”) is an alphabet written in order.

We haven’t seen any examples of the ampersand used in Old English other than in alphabets. The earliest examples we’ve found for the ampersand in actual text are in Middle English. Here’s an example from The Knight’s Tale of the Hengwrt Chaucer, circa 1400, one of the earliest manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales:

The middle line in the image reads: “hir mercy & hir grace” (“her mercy & her grace”). Here’s an expanded version of the passage: “and but i have hir mercy & hir grace, / that i may seen hire atte leeste weye / i nam but deed; ther nis namoore to seye” (“And unless I have her mercy & her grace, / So I can at least see her some way, / I am as good as dead; there is no more to say”).

Middle English writers also used the ampersand in the term “&c,” short for “et cetera.” In a 1418 will, for example, “&c” was used to avoid repeating a name: “quirtayns [curtains] of worsted … in warde of Anneys Elyngton, and … a gowne of grene frese, in ward, &c” (from The Fifty Earliest English Wills in the Court of Probate, edited by Frederick James Furnivall, 1882).

Although literary writers didn’t ordinarily use a symbol for “and” in early Modern English, the ampersand showed up every once in a while. For example, the character slipped into this passage from The Shepheardes Calender (1579), Edmund Spenser’s first major poem: “The blossome, which my braunch of youth did beare, / With breathed sighes is blowne away, & blasted.”

And in the 1603 First Quarto of Hamlet, Shakespeare has Hamlet telling Horatio, “O the King doth wake to night, & takes his rouse [a full cup of wine, beer, etc.].” But “and” replaces the ampersand, and the “O” disappears, in the Second Quarto (1604) and the First Folio (1623).

As for today, we see nothing wrong with using an ampersand in casual writing (we often use “Pat & Stewart” to sign our emails), but we’d recommend “and” for formal writing and noteworthy informal writing.

Nevertheless, formal use of the ampersand is common today in company names, such as AT&T, Marks & Spencer, and Ben & Jerry’s. And some authors, notably H. W. Fowler in A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926), have used them regularly in formal writing.

Finally, we should mention that the term “ampersand” is relatively new. Although the “&” character dates back to classical times, the noun “ampersand” didn’t show up in writing until the 18th century.

The earliest OED example for “ampersand” with its modern spelling is from a travel book written in the late 18th century. Here’s an expanded version:

“At length, having tried all the historians from great A, to ampersand, he perceives there is no escaping from the puzzle, but by selecting his own facts, forming his own conclusions, and putting a little trust in his own reason and judgment” (from Gleanings Through Wales, Holland and Westphalia, 1795, by S. J. Pratt).

The expression “from A to ampersand” (meaning from the beginning to the end, or in every particular) is an old way of saying “from A to Z.” It was especially popular in the 19th century.

As we’ve noted, the ampersand followed the letter “z” in some old abecedaria, a practice going back to Anglo-Saxon days. And when children were taught that alphabet in the late Middle Ages, they would recite the letters from “A” to “&.”

In Promptorium Parvolorum (“Storehouse for Children”), a Middle English-to-Latin dictionary written around 1440, English letters that are words by themselves, including the ampersand, are treated specially in reciting the alphabet, according to The Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories (1991), edited by Frederick C. Mish.

As Mish explains, when a single letter formed a word or syllable—like “I” (the personal pronoun) or the first “i” in “iris”—it was recited as “I per se, I.” In other words, “I by itself, I.”

“The per se spellings were used especially for the letters that were themselves words,” Mish writes. “Because the alphabet was augmented by the sign &, which followed z, there were four of these: A per se, A; I per se, I; O per se, O, and & per se, and.”

Since he “&” character was spoken as “and,” children reciting the alphabet would refer to it as “and per se, and.” That expression, Mish says, became “in slightly altered and contracted form, the standard name for the character &.” In other words, “ampersand” originated as a corruption of “and per se, and.”

The two earliest citations for “ampersand” in the OED spell it “ampuse and” (1777) and “appersiand” (1785). Various other spellings continued to appear in the 1800s—“ampus-and” (1859), “Amperzand” (1869)—before the modern version became established.

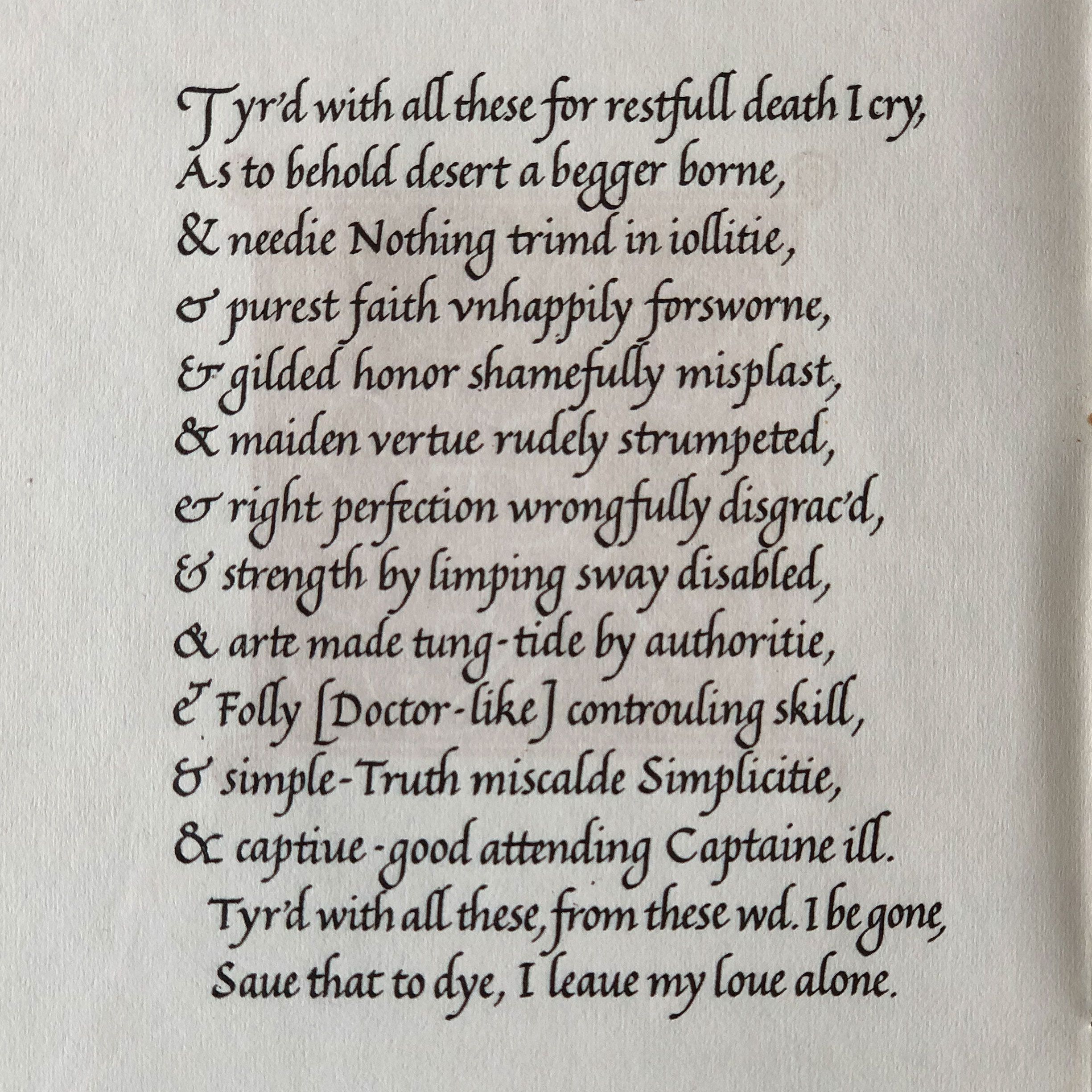

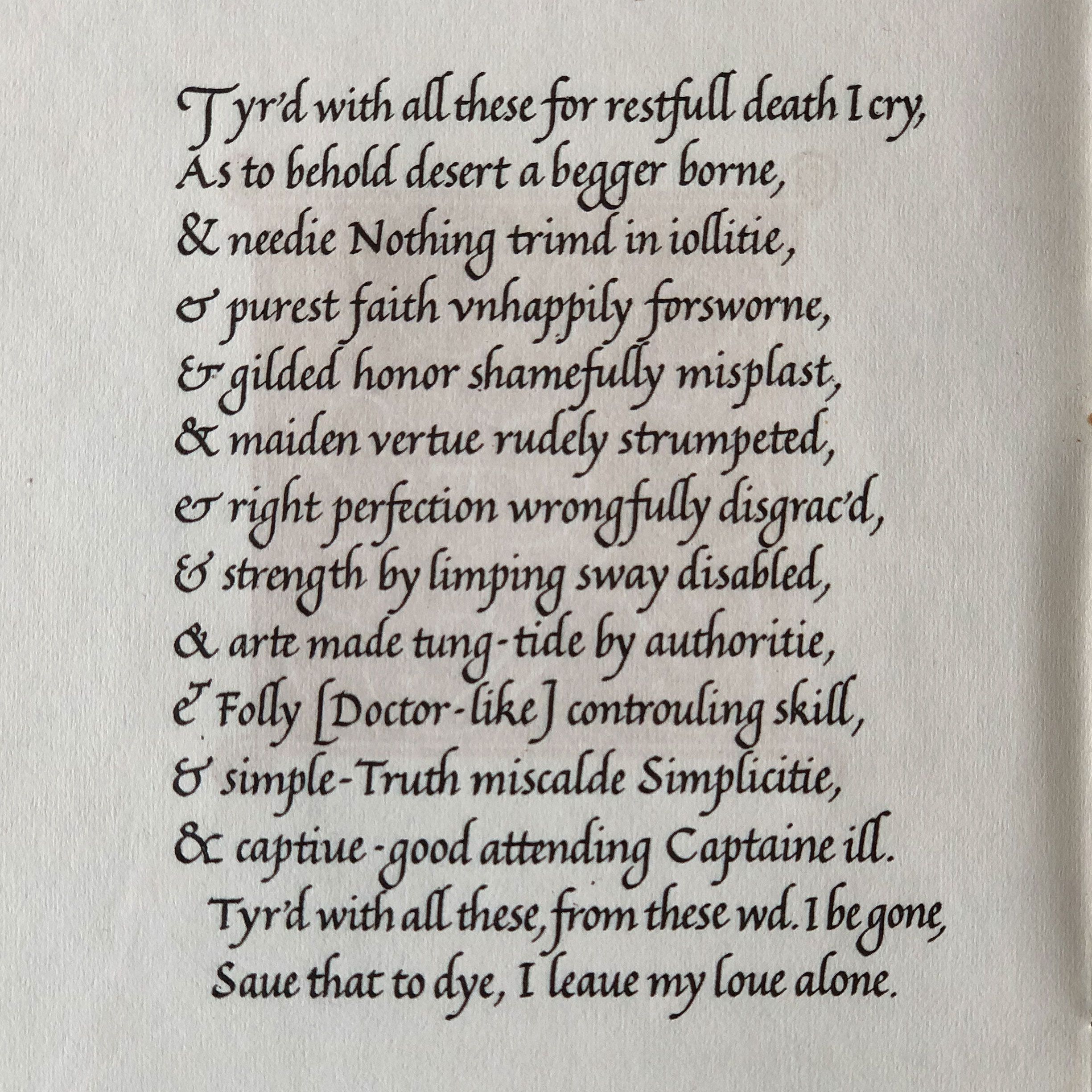

We’ll end with “The Ampersand Sonnet,” the calligrapher A. J. Fairbank’s take on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 66. In this version of the sonnet, each “and” in Shakespeare’s original is replaced by a different style of ampersand:

Help support the Grammarphobia Blog with your donation. And check out our books about the English language and more.